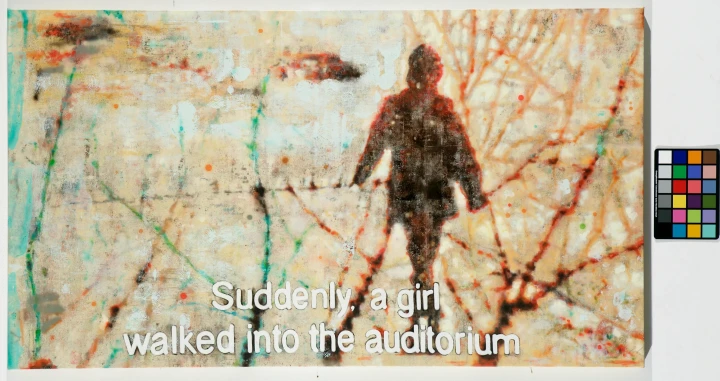

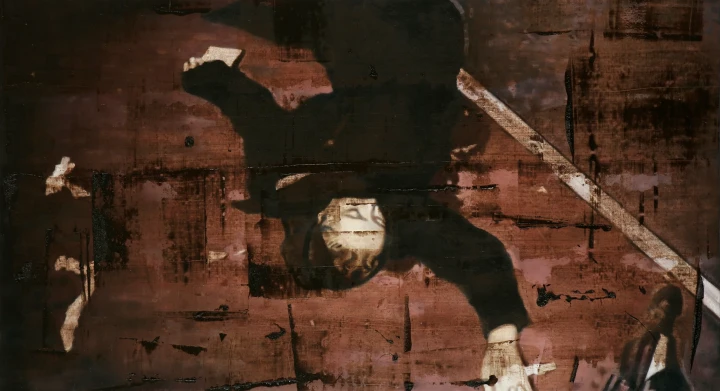

Another man appeared from the wings, also in military costume, and fired a weapon into the air. The audience at first believed this to be part of the performance. However, it didn’t take long for them to realize that this was not art but real life, and the beginning of what turned out to be a 57-hour ordeal from which many of them would never emerge alive. They were no longer an audience, but hostages. The brutality of the Chechen war for independence had been brought to the heart of Moscow.

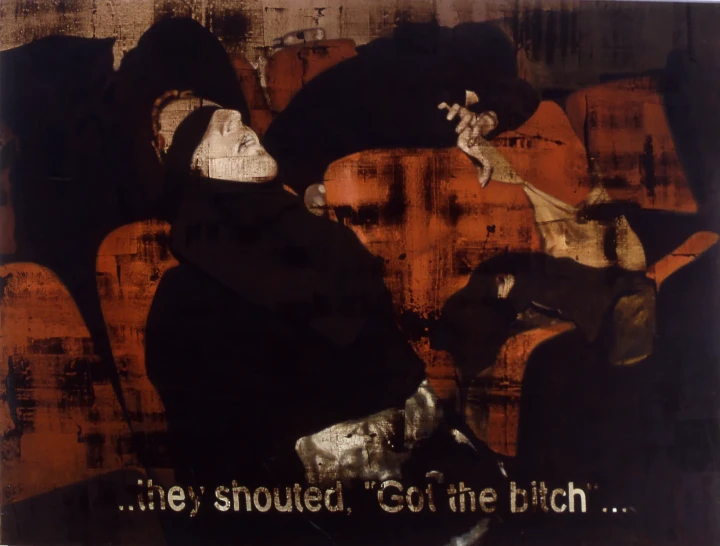

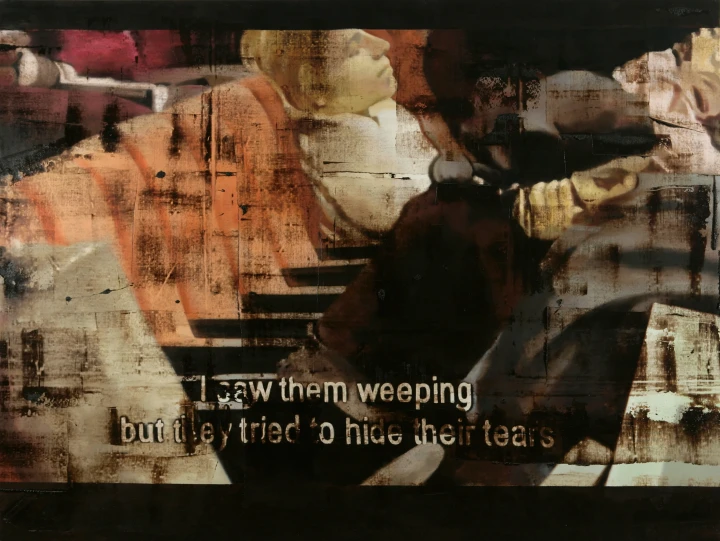

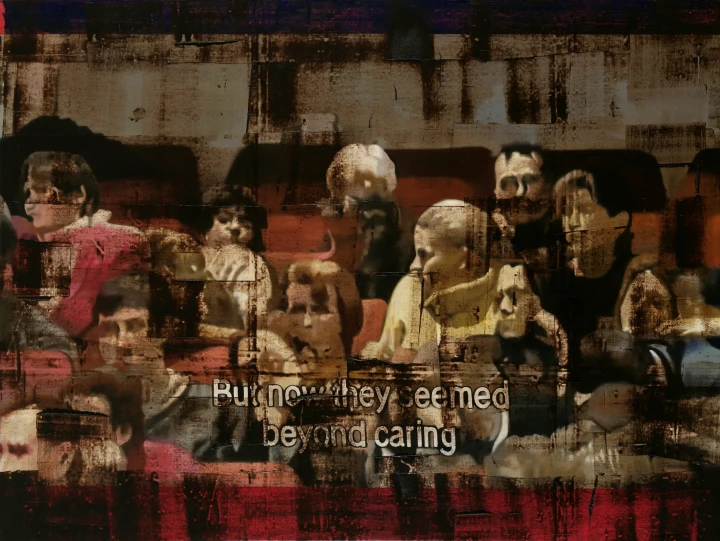

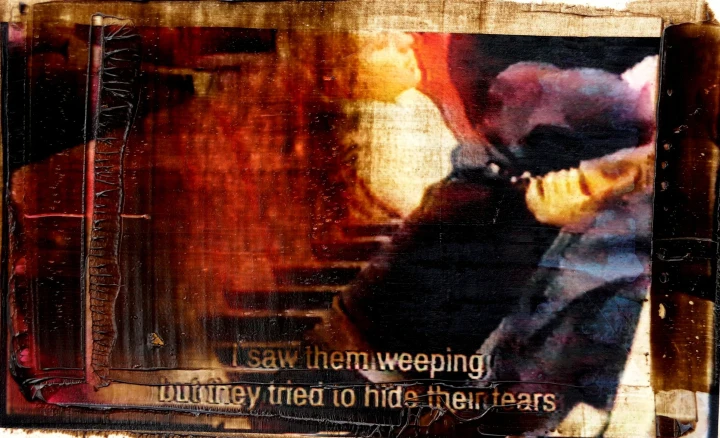

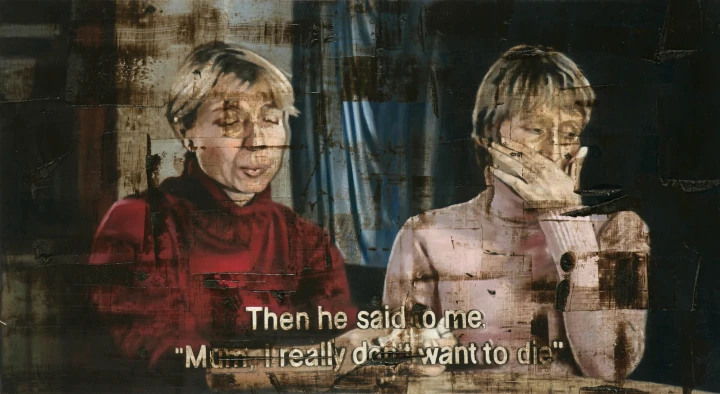

The tragedy of people inadvertently trapped in menacing events beyond their control (a situation now increasingly common) is underscored by the use of poignant subtitles of the translated Russian testimony.

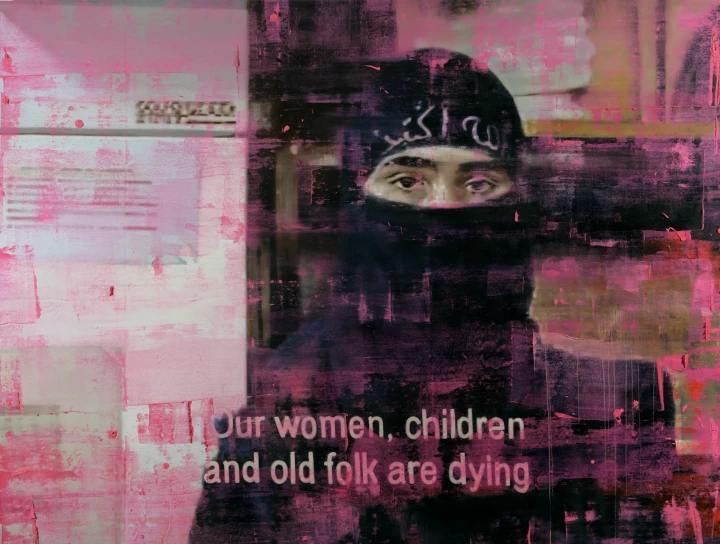

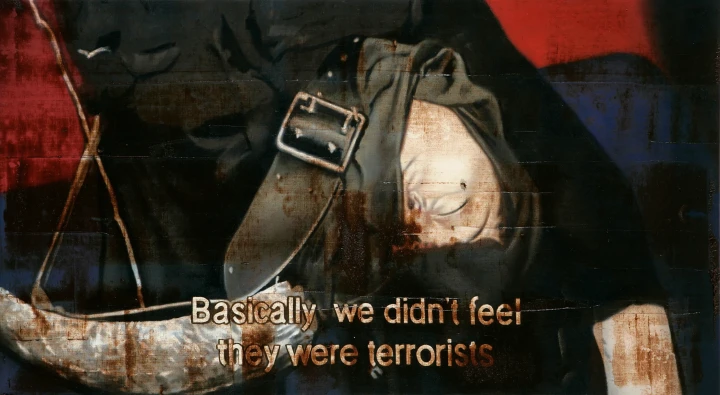

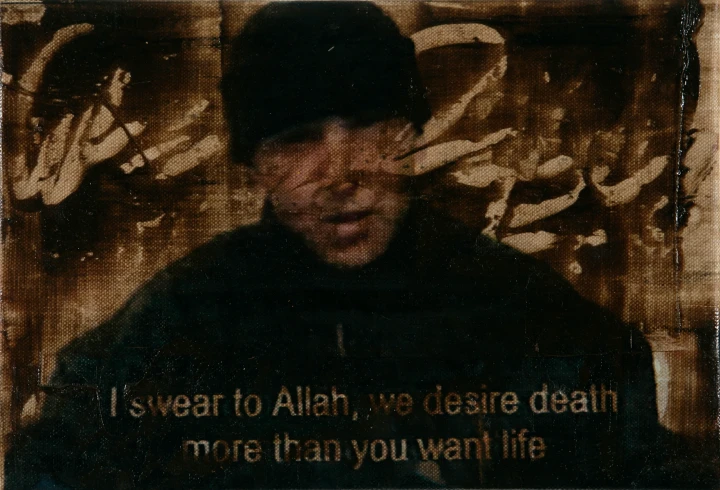

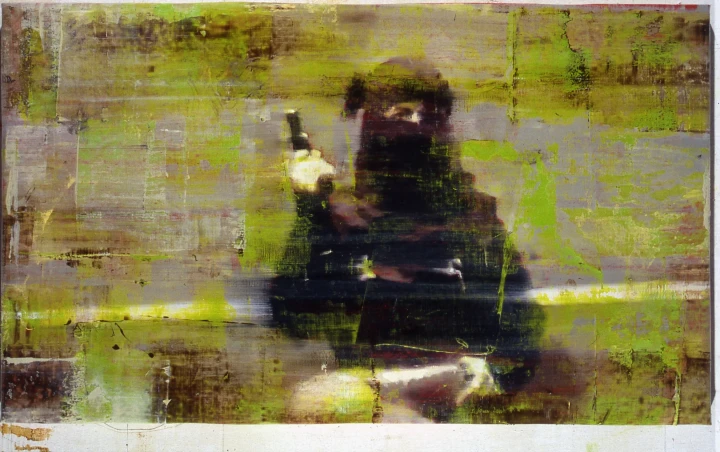

The paintings concentrate both on the Russian hostages in the audience, their fear and resignation, and also the female suicide bombers, the so-called ‘Black Widows’, who paced the aisles strapped with explosives where normally you might expect to see usherettes selling ice creams. The veil becomes the balaclava, as the Chechen struggle for independence morphs into Islamic jihad and becomes another convenient focus in the ‘war on terror’, left to the Russians and ignored in the West.

These women, too, as sisters and wives of Chechens killed or disappeared, can also be seen as historical victims as well as perpetrators of terror and tie in with a continuing theme in my work dealing with political violence justifying itself as self defense. My interest in the terrorist/freedom fighter paradox has previously taken me to Northern Ireland, Central America and more recently the Middle East.

Whilst these paintings depict a specific event related to a specific conflict a long way from London, the imagery alludes to the bubble of immunity which most of us occupy in our daily lives as we watch the world outside, literally screened off by our televisions, and how this bubble can now be so easily burst in the most brutal way by people and events that we feel have nothing to do with us. The reality is of course, as we have learned recently to our cost in London, it has everything to do with us.

Yuri Samodurov, the director of the Andrei Sakharov museum, writes:

Why after careful consideration I decided to show Keane's paintings at our museum? First because these paintings encourage empathy and respect towards those who survived the tragedy (one of them is a participant of our museum programs). Moreover the paintings bring about respect towards precious human life in general. Second it is important that some of Keane's subjects are terrorists that had all been killed even those who were unconscious and no one was left to interrogate to ask questions about the motives and the details of the attack. I believe that these people's answers would help to have prevented subsequent terrorist attacks (the one in Beslan School in 2004). Third the exhibition should be shown in Moscow in order to attract attention of Russian society to the fact that even if Chechen hostage takers were directly responsible for the tragedy and the resulting deaths Russian authorities have to share responsibility. I anticipate sharp criticism from Russian officials but I still believe that the government is partly responsible for this terrorist attack as well as for the other ones. And finally this exhibition will be a reminder of a crime that had been committed but had not been fully investigated and acknowledged. As Petra Weber an artist and the author of the previous exhibition at Andrei Sakharov Museum said. “We only become overwhelmed when we do nothing. Therefore we believe that this show will encourage many brave people - relatives and friends of Dubrovka victims their lawyers journalists and human rights fighters - the people who still insist on a true answer to a question: who was responsible for the death of 130 hostages and could their deaths have been prevented?