The scene from Love Actually shot in my studio in 2002..

Andrew Lincoln admits he loves Keira Knightley her in this rather creepy scene.. and somehow magically steps out through my Shoreditch doorway to find himself on the South bank of the Thames..

A selection of news, updates, thoughts etc.

Andrew Lincoln admits he loves Keira Knightley her in this rather creepy scene.. and somehow magically steps out through my Shoreditch doorway to find himself on the South bank of the Thames..

SEPTEMBER 2021.

It its now nearly forty years since I was able to renounce my previous short-lived careers as cleaner, waiter, civil service clerk or scenic painter to make a living solely from the sale of my own work.

Thoughts on the war in Ukraine, July 2023

–

Dreweatts, 16-17 Pall Mall St James’s London SW1Y 5LU

Online auction

By playing this video you are consenting to YouTube's privacy and cookie policy.

FAR OUT MAGAZINE September 2021

STUDIO SHOW AND SALE

By playing this video you are consenting to Vimeo's privacy and cookie policy.

–

Flowers Gallery, 21 Cork Street, London W1S 3LZ

Pleased to announce that FLAT EARTH, aborted before opening in March, will reopen in September under…

However there is a viewing room on the Flowers gallery website with images and a commentary by the artist accompanied by a soundtrack by Brian Eno

–

FLOWERS GALLERY, LONDON, Kingsland Road

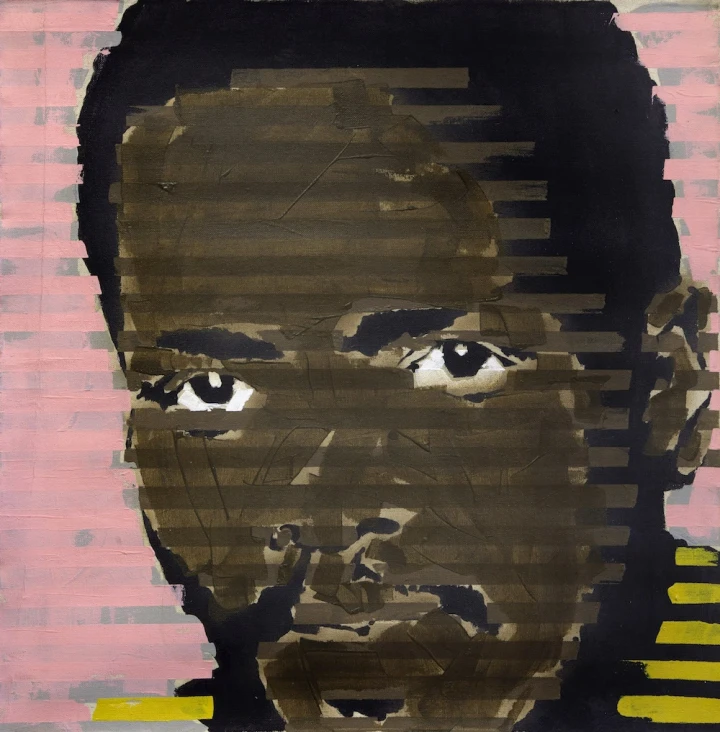

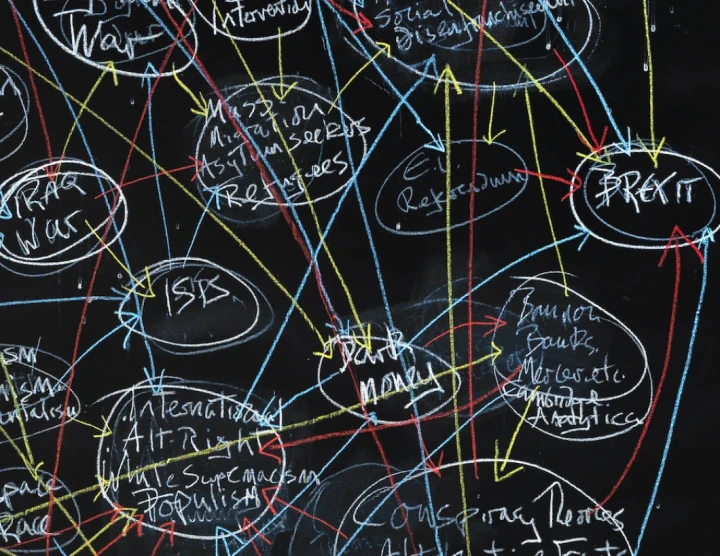

The collection of works in the exhibition Flat Earth have been created over the last two years amid …

De Grey Court Theatre,, York St John University, YO31 7EX

Painting Contemporary Thought

By playing this video you are consenting to YouTube's privacy and cookie policy.

John Keane discusses 'If You Knew Me. If You Knew Yourself. You Would Not Kill Me.' and 'At The Fron…